"Gaze Without Eyelids" by Marleen Stoessel

Translation into English: Bradley Schmidt

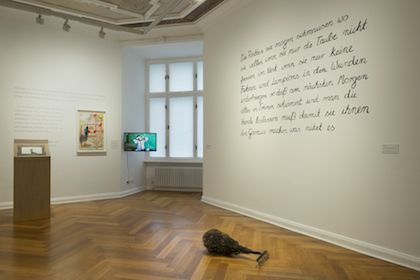

This exhibition is irritating, disturbing, touching, unleashing things below the surface. Eyes, and their witnessing, the gaze in the title. If one attempts to name an object as the heart of the exhibition, then one recognizes that almost each object represents the heart, because the center, which the heart characterizes, travels. It travels through the four rooms of the Zilberman Gallery, which only opened this Spring, but has its headquarters in Istanbul. Following this summer, with its first presentation of artists overwhelmingly from Turkey, this exhibition is the true inauguration. A strong sign, emphatic, quiet.

One of the “Hearts” of the collection shows a pair of glasses made up of two tin funnels by Memed Erdener alias Extramücadele (5,000 euros), the pointed tips directed towards the eyes. A pair of glasses that gives events a bloody filter: “The Red Gaze” – the title runs through like a “red thread”, even as a trail of blood through the rooms. This is reminiscent of the last self-portrait painted by Arnold Schoenberg through an early self-depiction: “The Red Gaze” from 1910, echoing the enflamed eyes of Munch’s “Scream”. But the one from 1944, now as if sketched with a child’s hand, is the terrible gaze of the famous composer in exile, the seemingly eyelid-less gaze back at the catastrophe he fled. The portrait is a loan from the Schönberg Center in Vienna. Using purchasable as well as unpurchaseable works, with pieces of German or foreign origin, and especially artists from the Middle East, the exhibition transcends the typical commercial framework. And not only that.

Once every year Moiz Zilberman gives himself the task of breaking through that corset and give an external curator free reign. In this case it was Almut S. Bruckstein Çoruh, scholar of Jewish Studies and curator who initiated the Taswir exhibition in Martin-Gropius-Bau in 2008, and in this instance also continued her concept, appropriating Aby Warburg and Talmudic hermeneutics: not only breaking through the boundaries of temporal and spatial belonging, but also the boundaries of genre itself, placing pictures, sculptures, written word, video and audio equally as witnesses of divergent origin and spheres, putting them in relation, in contrast and dialogue. With the gazes directed by Schoenberg through the funnel-glasses, to texts such as a poem by Picasso and translated by Celan, which travels across the walls as the other writings and quotes; travels on to the video “Wonderland” (7,200), which the Kurdish artist Erkan Özgen made of a deaf-mute boy named Mohammed in a Turkish refugee camp. The child had to watch with his own eyes how his cousins were decapitated and a part of his family massacred. In a true psycho-drama, the boy depicts the trauma with emphatic gestures and signs, recorded by the artist with the child’s agreement. A three-fold witnessing, a three-fold broken gaze is created: the child’s pantomimic depiction, who was the witness of the murder; the witness of the artist, who records the portrayal and passes it on to the observer, who is the third witness. A kind of seeing with eyelids cut off, as Kleist put it once.

Yet the viewers are not only appealed to on a moral and political level, but also the relationship to art, its notion itself, is shifting. Its origins in a cultic context are touched upon when the Paris-based Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis shows the Orthodox Christian rites in his “Icons” (34-52,000 euros) in self-designed lecterns. In this way, the exhibition becomes an echo chamber of connections, associations, commentaries, references, but also sub-currents in which the forms, bodies, gestures, and motifs are illuminated reciprocally from seemingly foreign connections. The idea is by no means new, but is currently unleashing effects and meanings in exhibitions such as the one by Alexander Ochs in the Berlin Cathedral, or the recently opening show “Uncertain States” in the Academy of Arts. At the same time, “The Red Gaze” casts a light on the extremely lively art scene in Turkey whose self-understanding – whether explicit or implicit – is political; where although Erdogan’s censorship might reach the large institutions and museums, it has not (yet) touched the incalculable diversity of urban creativity. These engage in a dialog with local-European perspectives or show, as with the Berlin-based artist Rebecca Raue, one’s own processing of foreign, past, or non-European inheritance. In an Egyptian-Syrian depiction from the 18th century that shows the greeting of an ascetic and his guest, Raue uses the exaggeratedly widespread arms in ironic play with a sun transformed into a solar orb that a cat appears to follow from above (12,000 euros). One of the few humorous moments in this “treasury of suffering” the exhibition focusses on.

But this treasury of suffering, which Warburg once wanted to rescue as “human possession of humanity” in his interminable image atlas, reaches its pinnacle here in a sculpture that also finds its place as a private loan in the last room: the torso of a “Cristo vivo” figure, a piece of Flemish ivory work from the 17th century. The corpus is maimed, robbed of its limbs, like an invalid war veteran, and of his cross. A comprehensive sign of a human martyrdom, which simply without the cross knows no religious and ethnic boundaries, no victim hierarchies, but appeals rather to Adam, the human, the man of Gezi, who in 2013 stood still and upright for hours among the advancing tanks and soldiers: “I am…”, the few words of the artist Erdem Gündüz, and they become a witness here.

Gazes can petrify, kill, destroy, exploit, and humiliate. But they can also open their eyes in the Other, and not least in art. Love, love, love – as a small swarm of birds, Rebecca Raue makes these words fly over her cheery image of greeting.

http://www.zilbermangallery.com/images/publications/The%20Red%20Gaze-Tagesspiegel_Stoessel.pdf

Marleen Stoessel: "Gaze without Eyelids"* („Lidloser Blick“)

Published in the Tagesspiegel, November 19, 2016.

*Headline in the online version of Tagesspiegel:

"Seeing as if with eyelids cut off" (“Sehen wie mit weggeschnittenen Augenlidern”)